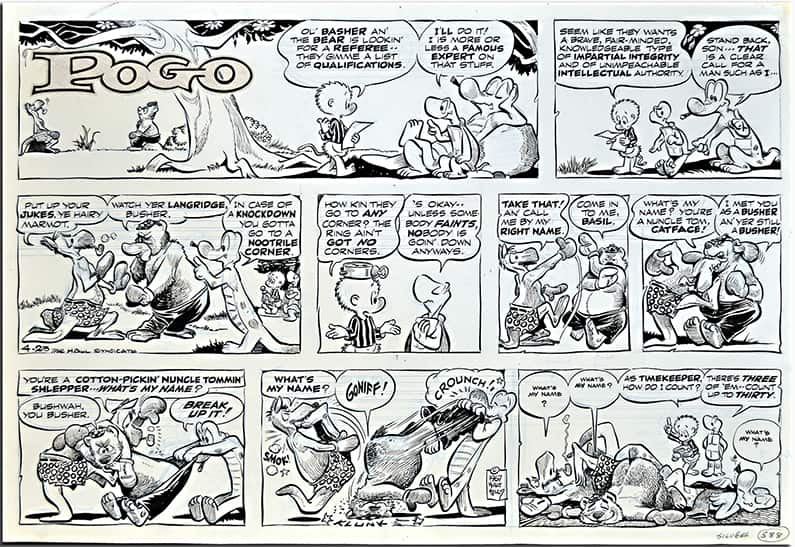

Walt Kelly debuted his comic strip POGO in the pages of the New York Star on October 4, 1948. The strip ran for the rest of the Star’s publication, which ended on January 28, 1949. But POGO returned, this time in syndication, on May 16, 1949. The early syndicated POGO strips seem familiar. Kelly took the 4 month layoff to redo most of the strips from POGO’s original run in the Star. His lines were bolder, and his storytelling became much more clear. This reaction to his own work belies his belief in total control of his product. Most, like myself, assumed that POGO first appeared in the pages of the Star. But Kelly’s characters had been appearing in comic book format for years prior. In fact, most of his work from that time is rare in today’s comic market. Kelly intended to bury this older work. In later years, Kelly misdirected his audience with a fake “first sketch” of Pogo Possum. He wanted POGO to appear as a fresh idea for the New York Star. This need for control made Kelly not only a shrewd entrepreneur, but also helped make him a masterful cartoonist.

Pogo Possum first debuted in the pages of Animal Comics in 1942. The character appeared in almost every issue of the title. There were also appearances in other Dell Comics, including a 16 issue Pogo Possum title. Kelly trained as a newspaper reporter and produced political cartoons or similar artwork. But it was his years working as an in-betweener at Walt Disney Studios that cut his cartooning chops. After leaving Disney to avoid choosing sides in a labor strike, Disney helped him find work back on the East Coast. He started at Western Printing and Lithographing Company, the publisher of both Disney and Dell comics.

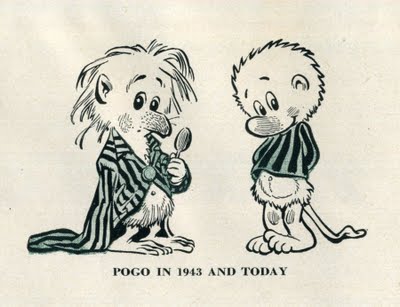

The evolution of Pogo Possum.

What’s most interesting about this early work is how much of it would recycle into the POGO syndicated strip. This was especially true for the Sunday strips. Since the Sunday strips contained more panels, it was easier for Kelly to translate his sequential pages to the new format. Another point of interest is to see the Pogo character transform from a secondary character to a leading everyman. Albert the Alligator was the protagonist for most of the early stories. Kelly’s art began to evolve as Pogo became the story focus. The character’s visual development skyrockets. The first appearance of Pogo and Albert are in the Disney style, with Pogo himself looking almost rat-like. While Albert’s design doesn’t change much over time, Pogo’s is transformed to a more pleasing one. He receives a more rounded head, larger eyes, and a streamlined body. In 1949, Pogo’s transformation was almost complete as we see it in later work. Kelly stripped away the rodent features to portray the character’s gentle and kind nature. Even Pogo’s tail no longer has a point at the end. Instead, the tail has a more rounded bump.

Pogo was appearing in both POGO in newspaper strips and in the Pogo Possum comic book, published by Western. Kelly felt frustrated producing the comic book and meeting deadlines as the strip’s popularity increased. His frustration only continued with Western trying to capitalize on his old work. Western published a collection of Kelly’s older POGO work from its Animal Comics stories. Kelly tried to fight its publication. He felt that it would confuse readers since the characters had changed in the decade of his telling their stories. Kelly was right. His readers thought he had hired assistants with little training to do new material for him. Kelly cancelled the series soon after to nullify his contract with Western. He was beginning to take control of his property.

This trend continued with his syndicate, Post-Hall. The syndicates owned the comic strips. But in 1952, Kelly wrestled his copyright back under his control. The comic strips started to attribute the copyright to Kelly. The distribution credit belonged to Post-Hall Syndicate. This put Kelly in an exclusive club of cartoonists who owned their creations. The deal meant that Kelly was a business partner with Post-Hall.

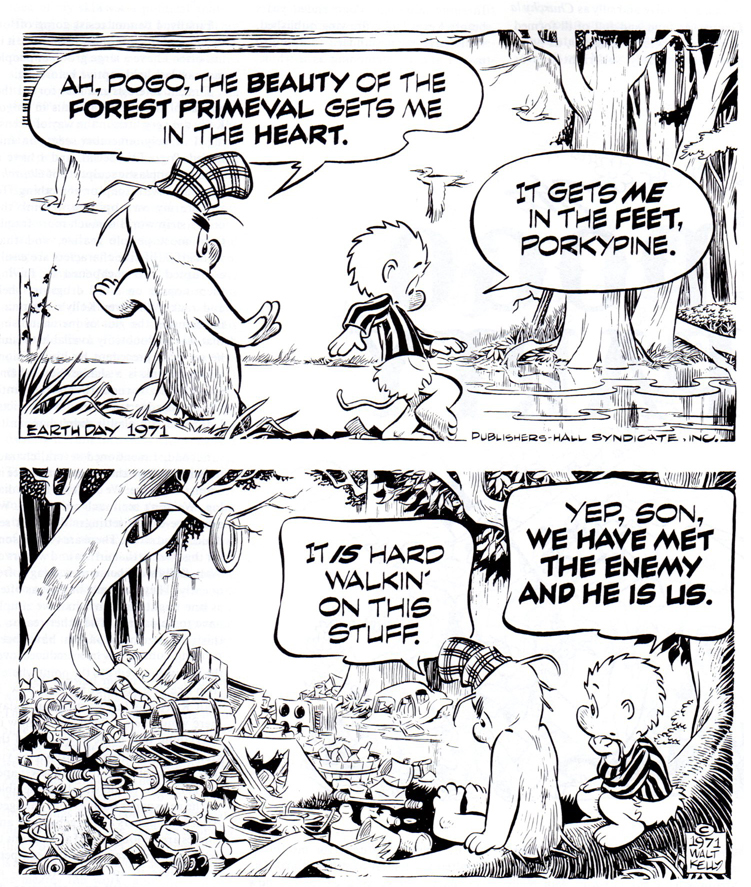

1971 Earth Day Poster

Another interesting facet of Kelly exerting control of the POGO property was political satire. The role of political lampooning was not seen in comic strips. This was the job for political cartoons on newspaper editorial pages. Post-Hall was reluctant for Kelly’s content to make this transition. But Kelly owned the strip. To placate the newspaper editors who found the move distasteful, Kelly accommodated them with alternate strips, like those he did for the holidays. Newspapers often did not print on the holidays back then as they did today. Not wanting to confuse the reader, Kelly would do separate strips for those papers who did publish on the holidays. Readers for any given paper were never in the dark or feeling like they missed a key strip.

As POGO’s popularity increased, the merchandising and licensing opportunities inundated Kelly. Again, we see Kelly using his business savvy to flat-out turn down almost every offer. He wanted to have complete control over his creation, and often did not have time to oversee these projects. This may have a correlation to the Disney Labor Strike that led to Kelly leaving the company. Walt Disney used to have daily contact with his workers, especially his animators. As the company grew, Disney had less time to interact with his employees. And the assembly line working conditions of animation caused the employees to gripe. When the animators formed a union and started a strike, the culture at Disney Studios suffered. It had permanent lasting effects on what the company produced in the years hence. Disney’s failure may have had a much more profound effect on Kelly. He had refused to choose a side; it may have taught him to always have personal control of his property.

Disney Animation Strike

Which isn’t to say that POGO was never used for promotional licensing purposes. Kelly was generous in using his work to support causes he believed in. He mentioned the importance of savings bonds in the content of his strip. Pogo appeared in promotional materials for the Salvation Army, the March of Dimes, and the Department of Labor. He even designed logos for military units. This was common practice at the time. Disney Studios produced a legion of these patches and logos for various armed service branches.

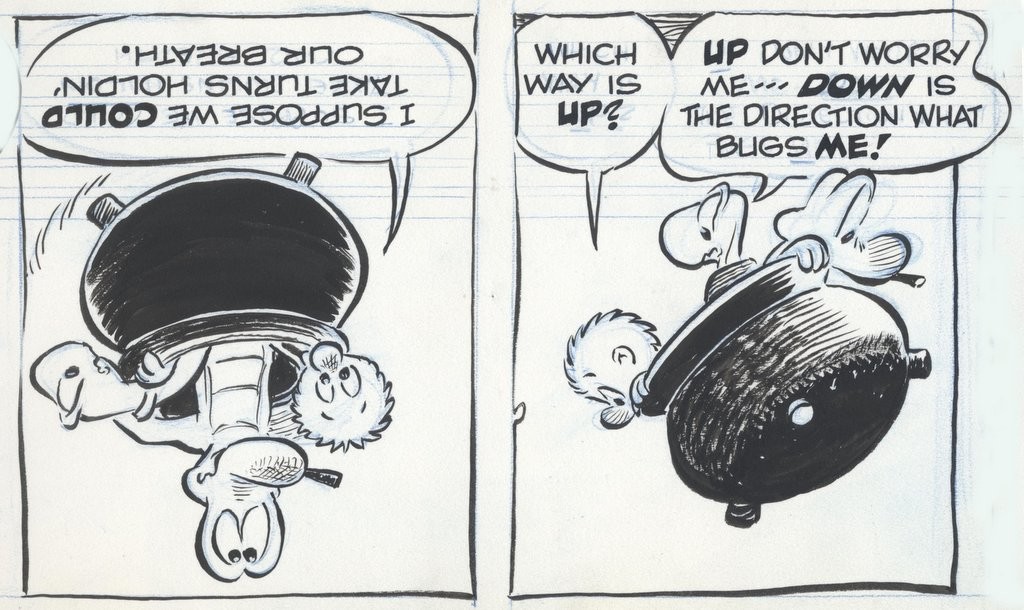

POGO was operating on a much higher level than many of the strips at the time. Kelly used every opportunity to experiment. The characters of the Okefenokee Swamp would often break the fourth wall and address the fact that they were inside a comic strip, in essence making the reader one of the characters. Kelly would introduce new characters on a regular basis. Some fans count around 600 characters before Kelly’s death. Kelly treated his characters almost as if they were actors on a stage. That, in combination with the bending rules of comic strip logic, made for some interesting strips.

Kelly’s art improved from his early Animal Comics days, as seen in his depiction of the Okefenokee Swamp. There was usually a great deal of care put into backgrounds for the first panel. It acts as an establishing environment shot. By the time POGO moved to newspapers, the backgrounds are both lush and minimal. There are definite visual hierarchies. A cluster of trees in the far background used spot black. But the foreground trees almost have more detail than the swamp inhabitants themselves.

As with most artists who use a brush to achieve long, lush lines for their figures, Kelly didn’t use an underdrawing. He chose to bring the characters to life with his brush instead. From studying his original pages, he roughed the characters out in blue line with simple geometric shapes. Kelly thought of each panel as more of a composition rather than talking heads.

From his time at Disney through years of sequential comic book work, Kelly became an artist who knew the value of quality. Combining this with his background as a journalist makes for an interesting pairing. Nothing is ever perfect in newspapers; there are always errors. It’s accepted as part of the business. Kelly took that mentality to his comic strip in much the same way Hergé did with TINTIN. He took what he learned from his earlier work and recycled his art through the lens of a more experienced cartoonist. He never aimed for perfection; he would save it for the next version, the next iteration. By having complete control over his creation, he was able to tweak and refine his stories to his heart’s content. After learning the rules and then breaking them, he didn’t hold a mirror up to the human condition, he created a window for us to take part in.